Author of “The Little Book of Revelation.” Get your copy now!!https://www.xlibris.com/en/bookstore/bookdetails/597424-the-little-book-of-revelation

447 posts

Gods Gender In Contextual Theology: Should We Preserve The Biblical Text In Light Of New Age Interpretations?

God’s Gender in Contextual Theology: Should We Preserve the Biblical Text in Light of New Age Interpretations?

By Bible Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

I’m all for women’s rights, and I admit that in heaven there is no gender (Gen. 1:26-27; Mk. 12:25). I also know that many members of the LGBTQ+ community have been **reborn** in God. It’s also true that the masculine form of God is sometimes added to the English Bible translations, as Bruce Metzger argues.

However, from a textual perspective, I disagree with the idea that every name of God in the Bible means God/dess in its original language, as some feminist theologians contend. Although conventional Jewish theology doesn’t ascribe the notion of sex to God, it’s clear that the gender of God in the Tanakh is presented with masculine grammatical forms & imagery. For example, in the Hebrew Bible, Elohim is masculine in form. Also, when referring to YHWH, the verb vayomer (“he said”) is definitely masculine; we never find vatomer, the feminine form. In Psalms 89:26, God is explicitly referred to as “Father”:

He shall cry unto me, Thou art my Father,

My God, and the rock of my salvation.

In Isaiah 63:16, God is directly addressed as “our Father":

Thou, O Jehovah, art our Father; our

Redeemer from everlasting is thy name.

The same holds true in the Greek New Testament. For example, Κύριος (Kyrios) is a Nominative Masculine Singular noun which means “Lord.” Θεὸς (Theos) is a Nominative Masculine Singular noun which means God. In Luke 1:68, the definite article ὁ (ho), which refers to the God of Israel (ὁ θεὸς τοῦ Ἰσραήλ), is a Nominative Masculine Singular (he). None of these phrases referring to the Lord (ό Κύριος) or to God (ό Θεός) have feminine forms in the original Koine Greek. Even the incarnated God is said to be male (see Rev. 12:5)!

However, many modern Bible translations furnish us with new additions, paraphrases, and grammatical forms that clearly deviate from the Biblical texts. They do not remain faithful to the original biblical languages in preserving their literal meanings. For example, there are numerous modern Bible translations——such as the NLT, the CEV, and the NRSV——which attempt to reword the original texts by adopting gender-neutral language. This is not simply a benign translation philosophy based on a feminist biblical interpretation, but it can also be seen as a tool for political activism in trying to change gender perceptions and alter the Bible’s authorial intent. This is theologically dangerous because when we tamper with the Bible’s grammatical structures we gradually lose the precise words of the revelations as they were given in their original forms. According to Wayne Grudem, the translator’s job is to translate the original language accurately and precisely rather than to offer opinions regarding gender-related questions.

The doctrine of verbal plenary inspiration——the notion that each word was meaningfully chosen by God——supersedes the cultural milieu by virtue of its inspired revelation. Therefore, the language from which the text is operating must be preserved without additions, subtractions, or alterations (cf. Deut. 4:2; Rev. 22:18-19). Accordingly, it is incumbent on the Biblical scholars to maintain the integrity of the text.

For example, since the mid-nineteenth century, the New Testament was not only significantly changed by the Westcott and Hort text but it has also been evolving gradually with culturally sensitive translations regarding gender, sexual orientation, racism, inclusive language, and the like. Contextual theology has broadened the scope of the original text by adding a whole host of modern political and socioeconomic contexts (e.g. critical theory, feminist theology, etc.) that lead to many misinterpretations because they’re largely irrelevant to the core message of the New Testament and the teachings of Jesus!

-

cr0w-with-a-knife liked this · 11 months ago

cr0w-with-a-knife liked this · 11 months ago -

hopefulparentingpastelopera liked this · 1 year ago

hopefulparentingpastelopera liked this · 1 year ago -

dxhighelf liked this · 2 years ago

dxhighelf liked this · 2 years ago -

koinequest liked this · 2 years ago

koinequest liked this · 2 years ago -

vain-imaginations liked this · 2 years ago

vain-imaginations liked this · 2 years ago -

ongawdclub liked this · 2 years ago

ongawdclub liked this · 2 years ago

More Posts from Eli-kittim

The Genesis Flood Narrative & Biblical Exegesis

By Bible Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

The Biblical Flood: Universal or Local?

Proponents of flood geology hold to a literal

reading of Genesis 6–9 and view its

passages as historically accurate; they use

the Bible's internal chronology to place the

Genesis flood and the story of Noah's Ark

within the last five thousand years.

Scientific analysis has refuted the key

tenets of flood geology. Flood geology

contradicts the scientific consensus in

geology, stratigraphy, geophysics, physics,

paleontology, biology, anthropology, and

archaeology. Modern geology, its sub-

disciplines and other scientific disciplines

utilize the scientific method. In contrast,

flood geology does not adhere to the

scientific method, making it a

pseudoscience. — Wikipedia

According to Bible scholarship, Noah is not a historical figure. And we also know that the legendary flood story of the Bible was inspired by an earlier epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, namely, “The Epic of Gilgamesh." Moreover, if we zero in on the mythical details of Noah’s Ark, the story has all the earmarks of a legendary narrative.

The Bible is an ancient eastern text that uses hyperbolic language, parables, and paradox as forms of poetic literary expression, akin to what we today would call “theology.” In the absence of satellites or global networks of communication, any catastrophic events in the ancient world that were similar to our modern-day natural disasters——such as the 2004 tsunami that killed 228 thousand people off the coast of Indonesia, or Hurricane Katrina, one of the most destructive hurricanes in US history——would have been blown out of proportion and seen as global phenomena. This would explain the sundry flood myths and stories that have come down to us from ancient times. And, according to Wikipedia:

no confirmable physical proof of the Ark

has ever been found. No scientific evidence

has been found that Noah's Ark existed as

it is described in the Bible. More

significantly, there is also no evidence of a

global flood, and most scientists agree that

such a ship and natural disaster would both

be impossible. Some researchers believe

that a real (though localized) flood event in

the Middle East could potentially have

inspired the oral and later written

narratives; a Persian Gulf flood, or a Black

Sea deluge 7500 years ago has been

proposed as such a historical candidate.

Bible Exegesis: Literal versus Allegorical Interpretation

My primary task, here, is not to weigh in on the findings of science as to whether or not a historical flood took place but rather to offer an exegetical interpretation that is consistent with the Biblical data. Taking the Bible literally——as a standard method of interpretation——can lead to some unrealistic and outrageous conclusions. For example, in Mark 9.50 (ESV), Jesus says:

Salt is good, but if the salt has lost its

saltiness, how will you make it salty again?

Have salt in yourselves, and be at peace

with one another.

Question: is Jesus literally commanding his disciples to carry salt with them at all times? In other words, is Jesus talking about “salt” (Gk. ἅλας) per se in a literal sense——the mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride——or is he employing the term “salt” as a metaphor to mean that his disciples should *preserve* their righteousness in this life of decay?

Obviously, Jesus is using the term “salt” as a metaphor for preserving godliness in the midst of a perishing world. This proof-text shows that there are many instances in the Bible where a literal rendering is completely unwarranted.

The Judgment of the Flood: There’s No Judgment Where There’s No Law

If one re-examines the flood story, one would quickly see that it doesn’t square well with history, science, or even the theology of the Bible. For example, Paul says in Romans that human beings became aware of sin only when the law was given to forbid it. But there is no judgment where there is no law. Romans 5.13 says:

for sin indeed was in the world before the

law was given, but sin is not counted where

there is no law.

So, my question is, if the law was given after Noah’s epoch, and if there was no law during Noah’s time, how could “sin … [be] counted [or charged against anyone’s account] where there is no law.”?

How, then, could God “judge” the world during the Pre-Mosaic law period? It would appear to be a contradiction in terms.

What is more, if we know, in hindsight, that no one is “saved” by simply following the law (Galatians 2.16) or by sacrificing animals (Hebrews 10.1-4), how could people possibly be “saved” by entering a boat or an ark? It doesn’t make any theological sense at all. But it does have all the earmarks of a mythical story.

The Flood as Apocalyptic Judgment

There’s no scientific evidence for a world-wide flood (Noah’s flood). Moreover, the Book of Revelation predicts all sorts of future catastrophic events and natural disasters that will occur on earth, where every island and mountain will be moved from its place, coupled with earthquakes, tsunamis, meteors, etc. The frequency & intensification of these climactic events is referred to as the “birth pangs” of the end times. In fact, it will be the worst period in the history of the earth! Matthew 24.21 puts it thusly:

For then there will be great tribulation,

such as has not been from the beginning of

the world until now, no, and never will be.

And since it is possible that Old Testament allegories may be precursors of future events, so the flood account may be alluding to an apocalyptic judgment. For example, if we examine and compare the series of judgments that Moses inflicted upon *Egypt* with the final judgments in the Book of Revelation, we’ll notice that both descriptions appear to exhibit identical events taking place: see e.g. Locusts: Exod. 10.1–20 (cf. Rev. 9.3); Thunderstorm of hail and fire: Exod. 9.13–35 (cf. Rev. 16.21); Pestilence: Exod. 9.1-7 (cf. Rev 6.8); Water to Blood: Exod. 7.14–24 (cf. Rev. 8.9; 16.3-4); Frogs: Exod. 7.25–8.15 (cf. Rev. 16.13); Boils or Sores: Exod. 9.8–12 (cf. Rev. 16.2); Darkness for three days: Exod. 10.21–29 (cf. Rev. 16.10). Apparently, the darkness lasts 3 symbolic days because that’s how long the “great tribulation” will last, namely, three and a half years (cf. Dan. 7.25; 9.27; 12.7; Rev. 11.2-3; 12.6, 14; 13.5). All these “plagues” are seemingly associated with the Day of the Lord (Mt. 24.29):

Immediately after the suffering of those

days the sun will be darkened, and the

moon will not give its light; the stars will fall

from heaven, and the powers of heaven will

be shaken.

In the same way, the Old Testament flood narrative may be representing a type of **judgment** that is actually repeated in the New Testament as if taking place in the end-times (cf. Luke 17.26-30): “Just as it was in the days of Noah, so will it be in the days of the Son of Man” (Luke 17.26)! In the Olivet prophecy, Mt. 24.39 calls the flood “a cataclysm” (κατακλυσμὸς) or a catastrophic event. And as 1 Pet. 3.20-21 explains, Noah’s flood is a “type” of the endtimes, and we are the “antitype” (ἀντίτυπον). As a matter of fact, in reference to the end-times destruction of Jerusalem, Dan. 9.26 says “Its end shall come with a flood.” In other words, there will be utter destruction and devastation, the likes of which the world has never seen before (Gen. 6.13; Dan. 12.1; Mt. 24.21).

Creation in 6 literal 24-hour days?

In Genesis 1.5, we are told that “there was evening and there was morning, the first day.” By comparison, Genesis 1.8 says “there was evening and there was morning, the second day.” What is puzzling, however, is that God made the moon & the sun on the 4th day (Genesis 1.14-19). How do you explain that?

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to realize that a literal 24-hour day model is inexplicable and does not seem to be part of the authorial intent. How could you possibly have mornings and evenings (or 24-hour “days”) if the sun & moon were formed on day 4? Obviously, they are not meant to be literal 24-hour days (see e.g. Gen. 2.4 in which the Hebrew word “yom,” meaning “day,” refers to the entirety of creation history). The creation days are therefore symbolic or figurative in nature.

Part of the internal evidence is that there are *allegorical interpretations* that are applied to scripture from within the text, such as 2 Peter 3.8, which reminds us of the following Biblical axiom:

But do not forget this one thing, dear

friends: With the Lord a day is like a

thousand years, and a thousand years are

like a day.

Similarly, Paul instructs us to interpret certain parts of the Bible **allegorically.** For example, Paul interprets for us certain Old Testament passages **allegorically,** not literally! Paul says in Galatians 4.22-26:

For it is written that Abraham had two sons,

one by a slave woman and one by a free

woman. But the son of the slave was born

according to the flesh, while the son of the

free woman was born through promise. Now

this may be interpreted allegorically: these

women are two covenants. One is from

Mount Sinai, bearing children for slavery;

she is Hagar. Now Hagar is Mount Sinai in

Arabia; she corresponds to the present

Jerusalem, for she is in slavery with her

children. But the Jerusalem above is free,

and she is our mother.

So, as you can see, there are not necessarily 6 literal days of creation, or 6,000 years in earth’s history, or a global flood, nor are there any talking donkeys holding press conferences and doing podcasts, there’s no evil that is caused by eating fruits, there are no trees of immortality on earth, no human angels wielding futuristic laser guns, and there are certainly no mythological beasts with seven heads walking around on park avenue in Manhattan. Proper Biblical exegesis must be applied.

But it’s equally important to emphasize that this allegorical approach to scriptural interpretation in no way diminishes the reliability of the Bible, its inerrancy, its divine inspiration (2 Tim. 3.16-17), or its truth values! The reason for that will be explained in the next two sections.

Biblical Genres Require Different Methods of Interpretation

The Bible has many different genres, such as prophecy, poetry, wisdom, parable, apocalyptic, narrative, and history. It is obviously inappropriate to interpret poetry or parable in the same way that we would interpret history because that would ultimately lead to logical absurdities. Alas, the history of Biblical interpretation is riddled with exegetes who have erroneously tried to force **parables and metaphors** into a **literal interpretation,** which of course cannot be done without creating ridiculous effects that you only encounter in sci-fi films. This view creates logical absurdities, such as talking serpents and talking donkeys, trees of immortality that are guarded by aliens with lightsabers, fruits literally producing evil after consumption, mythological beasts with multiple heads that are populating our planet, and the like. For example, the “beasts” in the Book of Daniel, chapters 2, 7, and 8, are interpreted by scripture as being symbolic of Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome. Similarly, the so-called “locusts” and “scorpions” in the Book of Revelation, chapter 9, seemingly allude to modern-day warfare. No one in their right mind would dare say that the beasts of Daniel or those of Revelation are **literal beasts.** Not only does this eisegesis defy the actual interpretation that is given by scripture itself, but it also leads to complete and utter nonsense.

Just as Ancient Philosophical Inquiry Was Discussed Through the Language of Poetry, So too Theological Truth Was Expounded Poetically in Sacred Scripture

It’s important to stress that a refutation of the historical flood narrative is not equivalent to a refutation of the “truths” of the Bible. The scriptural “truth values” work on many different levels. Truth can be presented in poetic form without necessarily compromising its validity.

For example, Lucretius’ only known work is a philosophical *poem* that is translated into English as “On the Nature of Things,” in which he examines Epicurean physics through the abundant use of poetic and metaphorical language. Similarly, the single known work by the Greek philosopher Parmenides——the father of metaphysics and western philosophy——is a *poem* “On Nature” which includes the very first sustained argument in philosophical history concerning the nature of reality in “the way of truth."

What is of immense interest to me is that both of these ancient philosophers explored their “scientific” and philosophical “truths” through the richly metaphorical language of *poetry*. So, why can’t the ancient books of the Bible do the same? Is modern science and literary criticism correct in dismissing biblical “truths” on historical grounds simply because of their richly poetic or metaphorical language? Perhaps our modern methodologies can be informed by the ancient writings of Lucretius and Parmenides!

Was Jesus Born Again?

By Goodreads Author Eli Kittim

Jesus’ Baptism in the Holy Spirit

In discussing Jesus’ baptism in the Holy Spirit, I’m not referring to John the Baptist’s water baptism. Rather, I’m referring to a Spirit baptism or a conversion experience where Jesus had a personal encounter with the power of God. Many Christian denominations emphasize that without such a “born-again” experience no one can enter the kingdom of God (Jn 3.5). From the outset, scripture emphasizes the need for a baptism of the Spirit (Mt. 3.11 NRSV):

‘He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and

fire.’

In Mk. 16.16-17, it’s not merely by faith alone but by spirit “baptism” that salvation is accomplished! Given that the born-again Christians “will speak with new tongues,” it’s clear that the text isn’t referring to a symbolic immersion in water but rather to a baptism of the Holy Spirit! And although Baptism is defined as a rite of admission into Christianity——by immersing in water——this ritual is *symbolic* of being cleansed from sin (1 Jn 1.7) by the death of the self. First Peter 3.21 (NIV) reads:

and this water symbolizes baptism that now

saves you also—not the removal of dirt from

the body but the pledge of a clear

conscience toward God.

In Rom. 6.3-4, Paul talks of a baptism Into Jesus’ death! It’s a believer’s participation in the death of Christ to allow them to “walk in newness of life.” It’s part of the same regeneration process which comprises the death of the old self & the rebirth of the new one (Eph. 4.22-24). The best example of Spirit baptism is in Acts 2.1-4! Colossians 2.12 (NIV) similarly says:

having been buried with him in baptism, in

which you were also raised with him through

your faith in the working of God.

Keep in mind that, in the gospel story, Jesus didn’t start his ministry prior to his regeneration. Nor was Jesus revealed prior to his rebirth. Mt. 3.16-17 (NRSV) suggests that Jesus’ regeneration began with John’s baptism and was followed thereafter by his encounter with the devil in the wilderness:

And when Jesus had been baptized, just as

he came up from the water, suddenly the

heavens were opened to him and he saw

the Spirit of God descending like a dove and

alighting on him. And a voice from heaven

said, ‘This is my Son, the Beloved, with

whom I am well pleased.’

This is a symbolic account of his rebirth. Notice that it was Jesus *alone* who saw (εἶδεν), presumably for the first time, the Spirit of God (cf. Jn. 3.3) who would later indwell him. If Jesus already had the Holy Spirit, there would have been no need for a temptation in the desert. Jesus already had the fullness of the Deity within him in bodily form (Col. 2.9) but, being innocent, he still had to receive the Holy Spirit in order to energize it and be transformed. The next verse says (Mt. 4.1 NRSV):

Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the

wilderness to be tempted by the devil.

This is a continuation of the earlier baptism motif in the previous chapter. If “ ‘John’s baptism was a baptism of repentance’ “ (Acts 19.4 NIV), as “Paul said,” then Jesus would have had to necessarily confront his sin nature at some point. For those who object to the notion that Jesus had a sin nature, how could he have been “like His brothers in every way” (Heb. 2.17), fully human, if he were unable to be tempted? Not to mention that it would also render the temptation pericope ipso facto meaningless because how could the devil tempt someone who is unable to be tempted by sin? That’s why scripture says that “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us” (2 Cor. 5.21 NIV)!

So, as part of his rebirth experience, Jesus had to confront the devil. That’s why the text emphasizes that he didn’t do it on his own. Rather, “he was led up [ἀνήχθη] by the Spirit.” Jesus then confronts the devil head on. He is persistently tempted in order that he may prove his loyalty to God. He faces various temptations and is put to the test. He experiences what the German Protestant theologian Rudolf Otto (1869–1937) calls the “mysterium tremendum”:

A great or profound mystery, especially the

mystery of God or of existence; the

overwhelming awe felt by a person

contemplating such a mystery (Oxford

English Dictionary).

The text shows that, by the end of his temptation experience, Jesus had been reborn in God by following the same principle as the one found in James 4.7 (NRSV):

Submit yourselves therefore to God. Resist

the devil, and he will flee from you.

Jesus does precisely that. Notice that the spirit of God and the angels did not minister to him prior to his rejection of Satan (Mt. 4.10-11 NIV):

Jesus said to him, “Away from me, Satan!

For it is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God,

and serve him only.’ “Then the devil left him,

and angels came and attended him.

This is a clear demonstration that even Jesus himself had to be reborn in order to both see & enter the kingdom of God (Jn. 3.3, 5). Given that he’s fully human (Heb. 2.17), he’s not exempt from the regeneration process, which is the necessary means by which a human being can become united with God.

This concept creates an obvious oxymoron. For example, if Christ was purportedly born-again, does this mean that Jesus got saved? Or that Jesus became a Christian? This is the kind of paradox that such an experience can suggest. In a certain sense, the answer is yes. Think about it. Being fully human, even Christ has to undergo a dangerous temptation in order to encounter God. But if that’s the case, then it means that there was a time when Jesus didn’t know God; a time when he didn’t have a personal and intimate relationship with him. Lk. 2.52 (NRSV) says:

Jesus increased in wisdom and in years,

and in divine and human favor.

If “Jesus increased in wisdom,” then this means that there was a time when he didn’t have much wisdom. The above verse also suggests that the divine favor towards him increased as Jesus got older. All these passages clearly show that Jesus grew up as a normal human being who underwent all of the spiritual experiences for regeneration and rebirth that we all encounter. He was not exempt from any of them, including that of regeneration & rebirth!

Conclusion

Scripture, then, shows that in being fully human, Jesus had to go through everything that we also face, including suffering, pain, depression, rejection, and so forth. Yet there are some pastors who teach that Jesus didn’t have a sin nature, never sinned, could not be tempted, was not reborn, and the like. Remember Isa. 53.3 (NLT)?:

He was despised and rejected— a

man of sorrows, acquainted with deepest

grief.

Yet in response to a Christian talk-show host, a famous preacher who heads a megachurch in Redding, California argued that Christ “wasn’t born again the way we’re born again.” Specifically, the Christian talk-show host posed the following question: So, “he [Christ] wasn’t born again the way we’re born again”? To which Christian minister and evangelist, Bill Johnson, replied: “No, goodness no, no. I have to be born again; he’s already God, so, absolutely not.” So much for pastoral care!

Erasmian vs. Modern Pronunciation: Philological & Linguistic Considerations

Researched by Eli Kittim

I’m not a linguist and I will not illustrate phonetic diagrams in philological nomenclature (e.g. IPA, etc.) lest I lose the audience's attention with such complicated jargon. I’m simply trying to understand the literature and summarize it in the best possible way. Since there’s not much interest in Ancient Greek pronunciation on the web, I compiled some material from a handful of links that might be of interest. Most of the paper is actually excerpted from various articles that are mentioned at the end of the paper.

——-

The History of the Reconstructed Pronunciation of Greek

“The study of Greek in the West expanded considerably during the Renaissance, in particular after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when many Byzantine Greek scholars came to Western Europe. Greek texts were then universally pronounced with the medieval pronunciation that still survives intact.

From about 1486, various scholars (notably Antonio of Lebrixa, Girolamo Aleandro, and Aldus Manutius) judged that the pronunciation was inconsistent with the descriptions that were handed down by ancient grammarians, and they suggested alternative pronunciations. This work culminated in Erasmus's dialogue De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (1528). The system that he proposed is called the Erasmian pronunciation. The pronunciation described by Erasmus is very similar to that currently regarded by most authorities as the authentic pronunciation of Classical Greek (notably the Attic dialect of the 5th century BC).” [1]

——-

The Reuchlinian Model

“Johann Reuchlin (1455 – 1522) was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew.” [2]

“Reuchlin, it may be noted, pronounced Greek as his native teachers had taught him to do, i.e., in the modern Greek fashion. This pronunciation, which he defends in De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (1528), came to be known, in contrast to that used by Desiderius Erasmus, as the Reuchlinian.” [3]

“Among speakers of Modern Greek, from the Byzantine Empire to modern Greece, Cyprus, and the Greek diaspora, Greek texts from every period have always been pronounced by using the contemporaneous local Greek pronunciation. That makes it easy to recognize the many words that have remained the same or similar in written form from one period to another. Among Classical scholars, it is often called the Reuchlinian pronunciation, after the Renaissance scholar Johann Reuchlin, who defended its use in the West in the 16th century.” [4]

“The theology faculties and schools related to or belonging to the Eastern Orthodox Church use the Modern Greek pronunciation to follow the tradition of the Byzantine Empire.” [5]

“The two models of pronunciation became soon known, after their principal proponents, as the ‘Reuchlinian’ and the ‘Erasmian’ system, or, after the characteristic vowel pronunciations, as the ‘iotacist’ (or ‘itacist’) and the ‘etacist’ system, respectively.” [6]

“The resulting debate, as it was conducted during the 19th century, finds its expression in, for instance, the works of Jannaris (1897) and Papadimitrakopoulos (1889) on the anti-Erasmian side, and of Friedrich Blass (1870) on the pro-Erasmian side.” [7]

“The resulting majority view today is that a phonological system roughly along Erasmian lines can still be assumed to have been valid for the period of classical Attic literature, but biblical and other post-classical Koine Greek is likely to have been spoken with a pronunciation that already approached that of Modern Greek in many crucial respects.” [8]

——-

Controversies about Reconstructions

“The Greek language underwent pronunciation changes during the Koine Greek period, from about 300 BC to 300 AD. At the beginning of the period, the pronunciation was almost identical to Classical Greek, while at the end it was closer to Modern Greek.” [9]

“The primary point of contention comes from the diversity of the Greek-speaking world: evidence suggests that phonological changes occurred at different times according to location and/or speaker background. It appears that many phonetic changes associated with the Koine period had already occurred in some varieties of Greek during the Classical period.” [10]

“An opposition between learned language and vulgar language has been claimed for the corpus of Attic inscriptions. Some phonetic changes are attested in vulgar inscriptions since the end of the Classical period; still they are not generalized until the start of the 2nd century AD in learned inscriptions. While orthographic conservatism in learned inscriptions may account for this, contemporary transcriptions from Greek into Latin might support the idea that this is not just orthographic conservatism, but that learned speakers of Greek retained a conservative phonological system into the Roman period. On the other hand, Latin transcriptions, too, may be exhibiting orthographic conservatism.” [11]

“Interpretation is more complex when different dating is found for similar phonetic changes in Egyptian papyri and learned Attic inscriptions. A first explanation would be dialectal differences (influence of foreign phonological systems through non-native speakers); changes would then have happened in Egyptian Greek before they were generalized in Attic. A second explanation would be that learned Attic inscriptions reflect a more learned variety of Greek than Egyptian papyri; learned speech would then have resisted changes that had been generalized in vulgar speech.” [12]

By the 4th century, “The pronunciation suggested here, though far from being universal, is essentially that of Modern Greek except for the continued roundedness of /y/.” [13]

Single Vowel Quality

“Apart from η, simple vowels have better preserved their ancient pronunciation than diphthongs. As noted above, at the start of the Koine Greek period, pseudo-diphthong ει before consonant had a value of /iː/, whereas pseudo-diphthong ου had a value of [uː]; these vowel qualities have remained unchanged through Modern Greek. Diphthong ει before vowel had been generally monophthongized to a value of /i(ː)/ and confused with η, thus sharing later developments of η. The quality of vowels α, ε̆, ι and ο have remained unchanged through Modern Greek, as /a/, /e/, /i/ and /o/. The quality distinction between η and ε may have been lost in Attic in the late 4th century BCE, when pre-consonantic pseudo-diphthong ει started to be confused with ι and pre-vocalic diphthong ει with η. C. 150 AD, Attic inscriptions started confusing η and ι, indicating the appearance of a /iː/ or /i/ (depending on when the loss of vowel length distinction took place) pronunciation that is still in usage in standard Modern Greek.” [14]

Consonants

“The consonant ζ, which had probably a value of /zd/ in Classical Attic (though some scholars have argued in favor of a value of /dz/, and the value probably varied according to dialects – see Zeta (letter) for further discussion), acquired the sound /z/ that it still has in Modern Greek, seemingly with a geminate pronunciation /zz/ at least between vowels. Attic inscriptions suggest that this pronunciation was already common by the end of the 4th century BC.” [15]

——-

A Critique of Erasmus’ Knowledge & Methadology

Erasmus “succeeded in learning Greek by an intensive, day-and-night study of three years.” [16] That’s hardly the time needed to become competent in Greek. What is more, he sometimes confused the Greek with the Latin:

“In a way it is legitimate to say that Erasmus ‘synchronized’ or ‘unified’ the Greek and the Latin traditions of the New Testament by producing an updated translation of both simultaneously. Both being part of canonical tradition, he clearly found it necessary to ensure that both were actually present in the same content. In modern terminology, he made the two traditions ‘compatible.’ This is clearly evidenced by the fact that his Greek text is not just the basis for his Latin translation, but also the other way round: there are numerous instances where he edits the Greek text to reflect his Latin version. For instance, since the last six verses of Revelation were missing from his Greek manuscript, Erasmus translated the Vulgate's text back into Greek. Erasmus also translated the Latin text into Greek wherever he found that the Greek text and the accompanying commentaries were mixed up, or where he simply preferred the Vulgate's reading to the Greek text.” [17]

His 1516 publication became the first published New Testament in Greek:

“Erasmus used several Greek manuscript sources because he did not have access to a single complete manuscript. Most of the manuscripts were, however, late Greek manuscripts of the Byzantine textual family and Erasmus used the oldest manuscript the least because ‘he was afraid of its supposedly erratic text.’ He also ignored much older and better manuscripts that were at his disposal.” [18]

So although the modern critical edition of the New Testament rejected Erasmus’ versions, those same scholars that sat on these editorial committees nevertheless adopted his pronunciation (odd)!

On the other end of the spectrum, Johann Reuchlin was a German Catholic who had no axe to grind. He neither defended the Eastern Orthodox Church nor the Greek heritage per se. So he had no conflict of interests. He didn’t have a dog in this fight, so to speak. His interest was purely intellectual and academic.

——-

German Reconstructions

“The situation in German education may be representative of that in many other European countries. The teaching of Greek is based on a roughly Erasmian model, but in practice, it is heavily skewed towards the phonological system of German or the other host language.

Thus, German-speakers do not use a fricative [θ] for θ but give it the same pronunciation as τ, [t], but φ and χ are realised as the fricatives [f] and [x] ~ [ç]. ζ is usually pronounced as an affricate, but a voiceless one, like German z [ts]. However, σ is often voiced, according like s in German before a vowel, [z]. ευ and ηυ are not distinguished from οι but are both pronounced [ɔʏ], following the German eu, äu. Similarly, ει and αι are often not distinguished, both pronounced [aɪ], like the similar German ei, ai, and ει is sometimes pronounced [ɛɪ].” [19]

“While the deviations are often acknowledged as compromises in teaching, awareness of other German-based idiosyncrasies is less widespread. German-speakers typically try to reproduce vowel-length distinctions in stressed syllables, but they often fail to do so in non-stressed syllables, and they are also prone to use a reduction of e-sounds to [ə].” [20]

French Reconstructions

“Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in French secondary schools is based on Erasmian pronunciation, but it is modified to match the phonetics and even, in the case of αυ and ευ, the orthography of French.” [21]

“Vowel length distinction, geminate consonants and pitch accent are discarded completely, which matches the current phonology of Standard French. The reference Greek-French dictionary, Dictionnaire Grec-Français by A. Bailly et al., does not even bother to indicate vowel length in long syllables.” [22]

“The pseudo-diphthong ει is erroneously pronounced [ɛj] or [ej], regardless of whether the ει derives from a genuine diphthong or a ε̄. The pseudo-diphthong ου has a value of [u], which is historically attested in Ancient Greek.” [23]

“Short-element ι diphthongs αι, οι and υι are pronounced … as [aj], [ɔj], [yj], [and] … some websites recommend the less accurate pronunciation [ɥi] for υι. Short-element υ diphthongs αυ and ευ are pronounced like similar-looking French pseudo-diphthongs au and eu: [o]~[ɔ] and [ø]~[œ], respectively.” [24]

“Also, θ and χ are pronounced [t] and [k]. … Also, γ, before a velar consonant, is generally pronounced [n]. The digraph γμ is pronounced [ɡm], and ζ is pronounced [dz], but both pronunciations are questionable in the light of modern scholarly research.” [25]

Italian Reconstructions

“Italian speakers find it hard to reproduce the pitch-based Ancient Greek accent accurately so the circumflex and acute accents are not distinguished. … β is a voiced bilabial plosive [b], as in Italian bambino or English baby; γ is a voiced velar plosive [ɡ], as in Italian gatto or English got. When γ is before κ γ χ ξ, it is nasalized as [ŋ] … ζ is a voiced alveolar affricate [dz], as in Italian zolla … θ is taught as a voiceless dental fricative, as in English thing [θ], but since Italian does not have that sound, it is often pronounced as a voiceless alveolar affricate [ts], as in Italian zio, or even as τ, a voiceless dental plosive [t]) … χ is taught as a voiceless velar fricative [x], as in German ach, but since Italian does not have that sound, it is often pronounced as κ (voiceless velar plosive [k]).” [26]

Spanish Reconstructions

Due to Castilian Spanish, “phonological features of the language sneak in the Erasmian pronunciation. The following are the most distinctive (and frequent) features of Spanish pronunciation of Ancient Greek: following Spanish phonotactics, the double consonants ζ, ξ, ψ are difficult to differentiate in pronunciation by many students of Ancient Greek, although ξ is usually effectively rendered as [ks]; … both vocalic quantity and vowel openness are ignored altogether: thus, no effort is made to distinguish vocalic pairs such as ε : η and ο : ω; the vowel υ, although taught as [y] (absent in the Spanish phonological system), is mostly pronounced as [i].” [27]

——-

What Do the Experts Say?

Nick Nicolas, PhD in Modern Greek dialectology & linguist at Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, outlines the 3 current pronunciation models of Ancient Greek:

1. Erasmus' reconstruction of Ancient Greek phonology, as modified in practice for teaching Greek in Western schools.

2. The scholarly reconstruction of Ancient Greek phonology.

3. Modern Greek pronunciation applied to Ancient Greek (“Reuchlinian" pronunciation). [28]

Nicolas’ Critique of Erasmian:

It's not quite fully there with the scholarly

reconstruction of Greek; so some of the

phonology and morphology of Ancient

Greek still doesn't make sense.

Particularly with diphthongs, and

aspiration, if your local Erasmian doesn't

do them accurately. [29]

“Extreme variability from country to country, because of the concessions each country's teaching system makes to the local language.

Speak in Erasmian to a Greek, and they'll look at you like a space alien. … But they will genuinely have no idea what you are saying, or what language you are saying it in. … It's quite far from Koine. Koine was still in flux, and some critical changes were underway when the bit of Koine most people care about (New Testament) was spoken. But overall, Koine was much closer to Modern Greek than Homeric.” [30]

——-

Here’s what Daniel Streett, Ph.D & Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Houston Baptist University, says about the pronunciations debate that occurred approximately 10 years ago at the annual Society of Biblical Literature meeting in San Francisco. It was sponsored by the Biblical Greek Language and Linguistics Section & the Applied Linguistics for Biblical Languages Group, which addressed the topic of Greek phonology and pronunciation.

Dr. Daniel Streett says:

“There is a widespread consensus among historical linguists as to how Greek was pronounced at its various stages. If you want a good summary of the consensus, check out A.-F. Christidis’ History of Ancient Greek, which has several articles on the various phonological shifts. Especially relevant is E.B. Petrounias’ contribution on ‘Development in Pronunciation During the Hellenistic Period’ (pp. 599-609).” [31]

Then he critiques the Erasmian Pronunciation that was presented by Daniel Wallace of Dallas Seminary. Dr. Streett writes:

“He was asked to argue for the Erasmian pronunciation, although, as he explained at the outset, he has no firm conviction that Erasmian pronunciation best reflects the way Greek was pronounced in the Hellenistic world.

I found Wallace’s presentation very easy to follow and enjoyable to listen to, but frustrating at the same time. I think he seriously misrepresented the state of our knowledge on Greek phonology in the Hellenistic and Roman imperial eras. He did not deal with any hard evidence from manuscripts or inscriptions (as subsequent presenters Buth and Theophilos did). He merely pointed out a few of the difficulties with assessing such evidence and then (IMO) cavalierly dismissed them.” [32]

Dr. Streett Comments on the Reconstructed Koine:

“Randall Buth of the Biblical Language Center presented third and advocated his reconstruction of 1st century Koine Greek. If you want a summary of his system, take a look at his page on it here: https://www.biblicallanguagecenter.com/koine-greek-pronunciation/

Buth’s presentation contained what Wallace’s lacked: a lot of evidence which demonstrated that however they were pronouncing Greek in the first century, it sure wasn’t Erasmian! Furthermore, he showed that the regional differences objection did not really hold, as the same sounds were ‘confused’ in texts from across the ancient world. So, while the pronunciation might have differed slightly from region to region, the phonemic structure remained stable.

Neo-hellenic or Modern Pronunciation

Michael Theophilos, who teaches at Australian Catholic University, presented last and advocated the modern pronunciation. Theophilos speaks modern Greek but also believes that most (or all?) of the modern phonology was in place by the first century. He made some very helpful methodological points. For example, he argues that we should be looking for phonological clues mainly in the non-literary papyri, which are more likely to contain phonetic spellings. He also offered several examples of iotacism in early papyri to show that there is at least some evidence that οι, η, and υ had iotacized by the 2nd century CE.

By the time you heard Simkin, Buth, and Theophilos, Wallace’s agnosticism seemed thorougly untenable. Theophilos didn’t have a whole lot to say about the practical reasons for using the modern pronunciation. I wish he would have, since it’s helpful for Erasmians to realize there’s an entire country of people who speak Greek and can’t bear to listen to the awful linguistic barbarity known as Erasmian. When Wallace was making the argument that Erasmians are by far in the pedagogical majority, he conveniently left out the millions of Greek students on this little peninsula in the Aegean.” [33]

——-

Conclusion

In the words of Daniel B. Wallace:

“Erasmian pronunciation is often considered cumbersome, unnatural, stilted, and ugly. The implication sometimes is that it must not have been the way Greek ever sounded; it is too harsh on the ears for that.” Not to mention fake and fabricated!

As regards Koine Greek, no one from our generation was there to hear the words being spoken. So no one really knows exactly how it sounded. But just as the closest pronunciation to Middle English is Modern English, so the rightful heir and descendant of Koine Greek pronunciation is obviously Modern Greek. It should be closer to the Koine Greek pronunciation than an invented phonetic system from the Renaissance. Just as Albert Schweitzer realized that most authors had interpreted Jesus in their own image, so Erasmians have interpreted Greek pronunciation in their own image as well. That’s why the Erasmian speakers don’t sound Greek but have the accents of their native countries.

What is more, many of their theories are erroneously based on Egyptian Greek papyri. Suppose that 2,000 years from now linguists try to reconstruct American pronunciation via English literature that was found in Australia. The pronunciations are vastly different. By comparison, what was spoken in Egypt or Palestine was certainly not spoken in Athens.

Besides, there’s much more literature on Erasmian pronunciation and a relative neglect or disinterest to write anything about the Reuchlinian or Modern Greek pronunciation. That’s a western bias that has been in place for centuries.

Let’s not forget that we learned so much about Koine Greek from the discoveries of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the like. The addition of approximately 5,800 New Testament mss. that we currently have just in Greek, compared to a handful that Erasmus had at his disposal, shows how much more equipped we are in understanding the intricacies and complexities of Koine Greek than he was in the early 1500s.

Philemon Zachariou——Ph.D Bible scholar, linguist, & native Greek speaker——uses various lines of evidence, including Plato’s writings, to show that ι = ει = η = [i] (kratylos 418c) is similar to Neohellenic Greek. He summarizes the evidence as follows:

“iotacism is not a ‘modern’ development but is traceable all the way to Plato’s day.” He further claims that “the phonemic sounds of mainstream Modern Greek are not ‘modern’ or new but historical; and the Modern Greek way of reading and pronouncing consonants, vowels, and vowel digraphs was established by, or initiated within, the Classical Greek period (500-300 BC).” [34]

He concludes that no pronunciation comes closer to Koine than Modern Greek.

Similarly, David S. Hasselbrook, who studies New Testament Lexicography, says that a number of new words that occur in the New Testament continue to have the same meanings in modern Greek. These words are closer to modern Greek than Classical Greek. Constantine R. Campbell, Associate Professor of New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, also says that Modern Greek helps to resolve text-critical issues related to pronunciation, whereas the Erasmian may lead down the wrong path! [35]

——-

Notes

1 Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching (Wiki).

2 Johann Reuchlin (Wikipedia).

3 Ibid.

4 Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching.

5 Ibid.

6 Ancient Greek phonology (Wikipedia).

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Koine Greek phonology (Wikipedia).

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Erasmus (Wikipedia).

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 What are the pros and cons of the Erasmian

pronunciation? (Quora).

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 The Great Greek Pronunciation Debate (SBL)

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Philemon Zachariou, PhD - YouTube Video

35 Ibid.

A Comparison Between Erasmian & Modern Pronunciation

Matthew 7 - Erasmian Pronunciation -https://youtu.be/vKrqwhBwur8

Matthew 7 - Modern Greek Pronunciation -https://youtu.be/ktmnpVzxPw4

——-

Selected Bibliography

Allen, William Sidney (1987). Vox Graeca. A Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Greek (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-521-33555-3. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

Jannaris, A. (1897). An Historical Greek Grammar Chiefly of the Attic Dialect As Written and Spoken From Classical Antiquity Down to the Present Time. London: MacMillan.

Papadimitrakopoulos, Th. (1889). Βάσανος τῶν περὶ τῆς ἑλληνικῆς προφορᾶς Ἐρασμικῶν ἀποδείξεων [Critique of the Erasmian evidence regarding Greek pronunciation]. Athens.

https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/1466927

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koine_Greek_phonology

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pronunciation_of_Ancient_Greek_in_teaching

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iotacism

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasmus

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Reuchlin

https://quora.opoudjis.net/2016/01/24/2016-01-24-what-are-the-pros-and-cons-of-the-erasmian-pronunciation/

https://danielstreett.com/2011/12/01/the-great-greek-pronunciation-debate-sbl-2011-report-pt-3/amp/

https://youtu.be/wYtrVlpnpg4

Who Is Eli Kittim & What Does He Believe?

By Award-Winning Author Eli Kittim 🎓

——-

Why Do I Write Under the Pseudonym of Eli of Kittim?

For the record, “Eli of Kittim” is my pen name, not my real name. I chose this name because it points directly to Jesus Christ himself. The name “Eli of Kittim” is a cryptic reference to Jesus, and it really means, “The God of Greece.” The idea that the Messiah’s name is Eli is mentioned in many passages of the Old and New Testaments. For instance, Matthew 27.46 defines the name “Eli” as God. It reads: “Eli, Eli ... that is, My God, my God.” Similarly, Daniel 12.1 refers to “the great [messianic] prince” named, “Michael” (Mika-el). Michael means “Who is like God?” But if you break-up the word, the prefix “Mika” means “who is like,” while “el,” the suffix, refers to God himself. The same holds in Matthew 1.23 where the author informs us that Jesus’ name is “Emmanuel," which means, "God is with us." Once again, the prefix is based on the root (im) עִם, which means “with,” while the root-suffix (el) אֵל means “God” (cf. Isaiah 7.14). This is probably why God says in Malachi 4.5 (DRB), “Behold I will send you Elias the prophet, before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord.” So, the common denominator in all these Biblical verses is that the Messiah is called Eli.

Moreover, Kittim is a repeated Old Testament Biblical name that represents the island of Cyprus, which was inhabited by Greeks since ancient times, and thus represents the Greeks. In Genesis 10.4 we are told that the Kittim are among the sons of Javan (Yavan), meaning Greece (see Josephus “Antiquities” I, 6). Even the War Scroll, found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, foretells the end-time battle that will take place between Belial and the King of the Kittim. This is all in my book, chapter 9. So, accordingly, Eli of Kittim roughly means, “The God of Greece.” That’s the name’s cryptic significance. And since the name Eli of Kittim represents the main argument of my book, I use it as my pen name!

——-

Bio

I’ve been involved in the study of serious Bible scholarship for over 30 years. I’m what you might call a Bible maven! I hold an MA degree in psychology from the New School for Social Research in New York City, and I’m also a graduate of the John W. Rawlings School of Divinity and of the Koinonia (Bible) Institute. I’ve also studied Biblical criticism at both Queens College and The New School (Eugene Lang). I’m fluent in Koine Greek, and I’m also a native Greek speaker. I also read Biblical Hebrew. I read the New Testament in the original languages. Currently, I’m a Bible researcher, published writer, and an award-winning Goodreads book-author. My book is called “The Little Book of Revelation: The First Coming of Jesus at the End of Days.” I advise all my readers to also read my *blog* because it furnishes *additional information* that usually answers most of their FAQs. I highly recommend that you read at least a few *related-articles* which flesh out certain ideas that are sometimes sparely developed in the book. It acts as a companion study-guide to “The Little Book of Revelation.” See Tumblr: https://eli-kittim.tumblr.com/

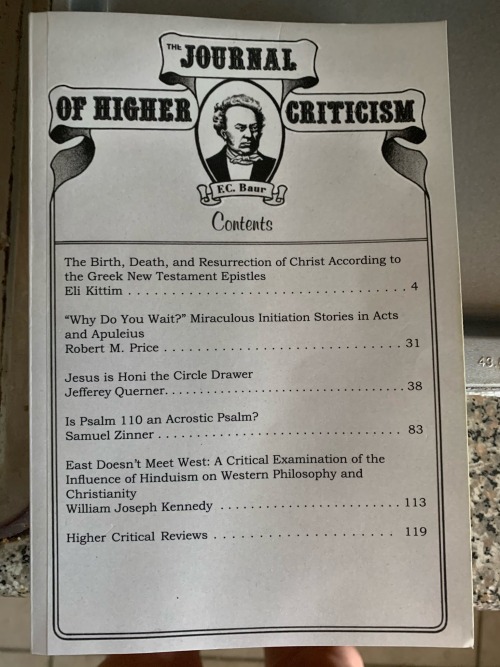

I have also contributed academic articles to numerous journals and magazines, such as “Rapture Ready,” the “Journal of Higher Criticism,” “The American Journal of Psychoanalysis,” and the “Aegean Review” (which has published works by Jorge Luis Borges, Lawrence Durrell, Truman Capote, Alice Bloom), among others.

——-

Rethinking Christianity: An Einsteinian Revolution of Theology

Just like Paul’s doctrine——which “is not of human origin; for … [he] did not receive it from a human source, … but … [he] received it through a revelation” (Gal. 1.11-12)——my doctrine was received in the exact same way! Mine is an Einsteinian revolution of theology. No one will do theology the same. I made 2 electrifying discoveries that turn historical Christianity on its head:

A) What if the crucifixion of Christ is a

future event?

B) What if Christ is Greek?

Both of these concepts were communicated to me via special revelation! Hermeneutically speaking, they involve an absolutely groundbreaking paradigm shift! Mine is the only view that appropriately combines the end-time messianic expectations of the Jews with Christian scripture! And most of the Biblical data, both academic and otherwise, actually supports my conclusions. The fact that it’s new doesn’t mean it’s not true. This new hermeneutic is worthy of serious consideration. No one has ever said that before. This can only be revealed by the spirit!

Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote:

All truth goes through three stages:

At first it is ridiculed.

In the second, it is violently rejected

In the third, it is accepted as self-evident.

I would suggest that readers do their due diligence by investigating my extensive writings in order to examine what my view is all about and on what grounds it is established.

——-

Kittim’s Systematic Theology

I have written about my systematic theology many times before, but only vis-à-vis my evidence (i.e. in trying to prove it). But I’ve never tried to clarify its foundations. In systematic theology, a theologian seeks to establish a coherent theoretical framework that connects all the diverse doctrines within a tradition, such as Bibliology, Soteriology, Eschatology, and the like. However, one of the major problems involved in such a study is the theological bias of the researcher who might “force” the data to fit the theory in an attempt to maintain coherence and consistency.

So, where does my systematic theology come from? I’m neither Protestant, nor Catholic, nor Eastern Orthodox (though I used to be Greek-Orthodox). I don’t belong to any particular church or denomination. Nor am I trying to create one. I’m rather selective, but I don’t identify with the various denominations of whose views I sometimes embrace. The reason is that——although I may agree with certain theological positions, nevertheless——I do not necessarily agree with their overall systems.

Unlike most other systematic theologies that are based on probabilities and guesswork, the starting point of my system is based on “special revelation”! This revelation, or rather these revelations (for I’ve had a number of them through the years) do not add any new content to the canon of scripture, but they do clarify it, especially in terms of chronology or the timing and sequence of certain prophetic events. So they don’t add anything new to the Biblical canon per se. The only thing they do change is *our interpretation* of the text. Incidentally, this revelation has been multiply-attested and unanimously confirmed by innumerable people. Due to time constraints, I can’t go into all the details. Suffice it to say that a great multitude of people have received the exact same revelation! Essentially, this is my spiritual navigation system. But I never force it on the text. I always approach the text with impartiality in order to “test the spirits,” as it were. The last thing I want to do is to engage in confirmation bias.

And my views fit all the evidence. For example, I agree with Biblical scholarship that most of the Old Testament is not historical. I fully agree that many of the Patriarchs did not exist. I concur that the same holds true for the New Testament, but not to the same degree. What is more, I’m in full agreement that the gospels are anonymously written, and that they’re nonhistorical accounts that contain many legendary elements. I further concur that the gospel writers were not eyewitnesses. I also agree with many credible Bible scholars who question the historicity of Jesus, such as Robert M. Price and Kurt Aland. I admit that some of the New Testament texts involve historical fiction. And I don’t believe that in order to have a high view of scripture one has to necessarily accept the historicity of the Bible, or of Christianity for that matter. Rudolf Bultmann was right: the Bible sometimes mythologizes the word of God!

——-

The High Quality of My Work

The truth is, I demand of my work nothing less than the highest possible quality so that it is able to withstand the rigors of modern scholarship! To that end, a solution to a particular problem must be multiply-attested and unanimously confirmed by all parts of Scripture, thus eliminating the possibility of error in establishing its legitimacy. I’m very comprehensive in my work and I use a very similar quasi-scientific method when interpreting the text. In order to avoid the possibility of misinterpretation during the exegetical process, I observe exactly *what* the text says, exactly *how* it says it, without entertaining any speculations, preconceptions, or presuppositions, and without any theological agendas. This eliminates any personal predispositions toward the text while preserving the hermeneutical integrity of the method.

And then I translate it into English with the assistance of scholarly dictionaries and lexicons. After that, I cross-reference information to check for parallels and/or verbal agreements. Thus, the translation of the original biblical languages becomes the starting point of my exegesis. This type of approach is unheard of. Almost everyone comes to the text with certain theological preconceptions. I’ve been heavily influenced by my academic and scientific backgrounds in this respect, and that’s why I’m very demanding and always strive to achieve the highest possible quality of work! I take a lot of pride in my work! And it is only after this laborious process has been completed that I finally check it against my original “blueprints”——namely, my revelations——to see if they match. It’s an airtight case because it’s not guided by speculation and conjecture, as most theologies seem to be.

The best explanation of my views comes from the following work. This is the pdf of my article——published in the Journal of Higher Criticism, volume 13, number 3 (Fall 2018)——entitled, “The Birth, Death, and Resurrection of Christ According to the Greek New Testament Epistles”:

https://acrobat.adobe.com/link/review?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:6b2a560b-9940-4690-ad29-caf086dbdcd6

——-

OPEN ACCESS AND THE BIBLE: The Bible and Interpretation

This is Eli Kittim’s academic monograph——published in the Journal of Higher Criticism, vol. 13, no. 3 (2018), page 4—-entitled, "The Birth, Death, and Resurrection of Christ According to the Greek New Testament Epistles."

To view or purchase, click the following link:

https://www.amazon.com/Journal-Higher-Criticism-13-Number/dp/1726625176

_______________________________________________